The Arts & STEM: Women Who Did Both (Pt. 1)

"Why would you want to study art? What a waste of money—they call them 'starving artists' for a reason."

"Artists are the ones bringing creativity to the world, touching peoples' hearts—not those engineers, those scientists."

Regardless of which field you leaned towards, you've likely heard these kinds of remarks before: STEM majors sneering at the "non-intellectual" humanities; humanities majors turning their noses up against the "uncreative" STEM field. This phenomenon, as highlighted in C.P. Snow's "Two Cultures" lecture, demonstrates a broad cultural divide between STEM and the humanities.

While Snow's lecture is more sympathetic towards the science side, the humanities world still receives injust stereotypes among the STEM community. "Art major" has become a taboo among many STEM circles, and the division of "hard science" vs. "soft science" further reinforces the false sense of intellectual superiority associated with fields such as chemistry, physics, and engineering.

As someone involved in both STEM and the arts, I've heard the animosity from both sides. But does being a programmer make one less of a poet? Does being an artist make one less of an engineer?

These women prove that the answer is "no." Expertise in multiple fields serves only to enhance—not negate—your other skills.

It's April now, and we've come to the conclusion of women's history month, but that certainly doesn't end our celebrations of our lovely ladies of STEM. In this post, we'll be talking about three women who defied the STEM vs. humanities divide and mastered disciplines in both fields.

___

|

| Merian in 1705: The Hague, National Library of the Netherlands |

Maria Sibylla Merian

Today, April 2, we celebrate the birthday of Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717), German-born naturalist, botanist, entomologist, and nature artist. Her observations provided valuable insights into science and medicine, and she unearthed discoveries about plants and insects that weren't previously known—during her time, people thought that insects were spontaneously born from the mud!Merian studied painting under her stepfather, still-life painter Jacob Marrel. As a child, she gathered insects for his paintings, inciting a lifelong fascination with nature. She proceeded to start her own caterpillar collection to study their metamorphosis into butterflies.

Merian's earlier works include a three-volume series of watercolor flowers and two volumes depicting the phases of metamorphosis of moths and butterflies. Her most well-known work stems from her research in Suriname, a country on the northeastern coast of South America. She and her daughter Dorothea Maria embarked for Suriname in 1699. The two women collected research on the country's flora and fauna and planned on staying for five years; however, after two years Merian fell ill and had to return to Amsterdam.

|

| Depiction of a tarantula devouring a bird: Maria Sibylla Merian, Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium, Amsterdam 1705, The Hague, National Library of the Netherlands |

The surprising observations Merian illustrated—like that of a tarantula devouring a bird—were mocked and dismissed as the work of a "silly woman." Her illustrations were poorly reproduced, her name forgotten, her illustrations criticized for their mistakes.

While Merian's illustrations did have their inaccuracies, biologist Kay Etheridge doesn't believe these flaws negate their merits. "These errors no more invalidate Ms. Merian’s work than do well-known misconceptions published by Charles Darwin or Isaac Newton," she says. Merian's works have since been re-printed and re-validated, their author re-gaining the acclaim she had upon publication.

|

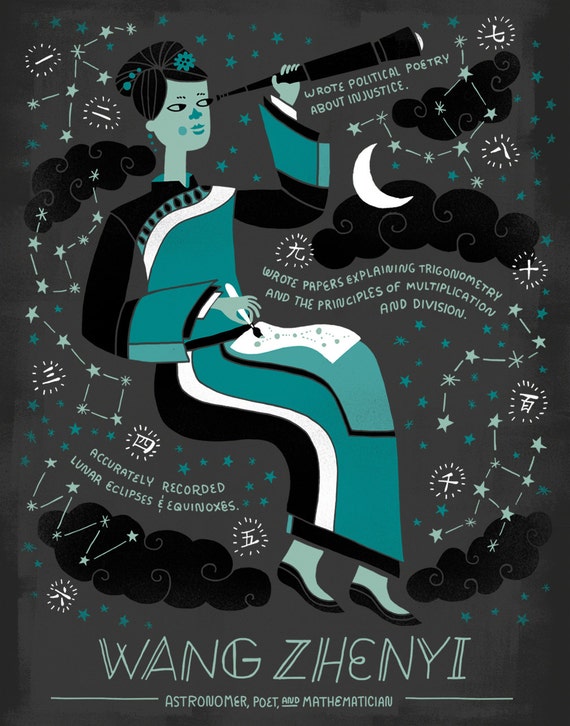

| Wang Zhenyi: Women in Science by Rachel Ignotofsky |

Wang Zhenyi

During the Qing Dynasty in China, eclipses were regarded as signs of angry gods. Astronomer, mathematician, and poet Wang Zhenyi (1768-1797) unraveled the myths behind these celestial phenomenons with her studies, writings, and demonstrations."Wang grew up in a family of scholars. Her father taught her about medicine, mathematics, and geography, her grandmother taught her about poetry, and her grandfather taught her about astronomy. As a child, she pored avidly over her grandfather's books; as a teenager, she traveled with her father around modern-day Nanjing and met many female scholars who helped her develop her poetry.

After her childhood, Wang was largely self-taught. Although her studies were difficult, her passion for knowledge drove her to continue. She once confessed, "There were times that I had to put down my pen and sighed. But I love the subject, I do not give up." Her setbacks made her realize how important it was for knowledge to be clear and accessible and not just for the upper-class, so she began to focus on making complex mathematical treatises easier to understand. She re-wrote Mei Wendling's Principles of Calculation, developed simplified methods of multiplication and division for beginners, wrote papers about gravity, astronomy, and trigonometry, and even tutored male students—shocking for a woman in her time.

Wang famously demonstrated the theory behind a lunar eclipse using a lamp representing the sun, a mirror representing the moon, and a round table representing the earth. She moved her "celestial bodies" to model the paths of the sun and the moon in the sky to explain that lunar eclipses occurred when the moon passed into the Earth's shadow. She proceeded to write an article, "The Explanation of a Lunar Eclipse," which is still considered highly accurate for her time period.

Wang's experience as a woman during a misogynistic, feudal society led her to realize that men and women had the same desire to learn, yet had unequal opportunities to do so. She was deeply frustrated that "when talking about learning and sciences, people thought of no women." Wang expressed her ideas in her poems, which addressed social issues and were considered unstereotypically feminine for their directness and lack of flowery words.

In one poem, she wrote, "It's made to believe, / Women are the same as Men; / Are you not convinced, / Daughters can also be heroic?"

Unfortunately, most of Wang's works have been lost to time, but her legacy as an accomplished, prolific woman and a progressive thinker still stands. In 2004, the International Astronomical Union honored her with a crater on Venus bearing her name.

|

| Hedy Lamarr: Alfred Eisenstaedt, The LIFE Picture Collection, Getty Images |

Hedy Lamarr

Most of us know Hedy Lamarr (1914-2000) for being the "world's most beautiful woman," but she was not only beautiful but a brilliant inventor as well. When she was young, her father would take her on walks and tell her about the inner workings of machines; at age five, Lamarr's parents would find her taking apart and reassembling her music box to see how it worked.Because of her beauty, her intelligence was often overlooked. Lamarr gained recognition for her role in the controversial 1932 film Ecstasy. She married Fritz Mandl in 1933, but quickly became unhappy with the way he treated her—she was forced to play housewife before Mandl's business partners, even those associated with the Nazi party, despite her Jewish descent.

Lamarr fled to London where she met Louis B. Mayer, head of the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) studio. This meeting launched her into Hollywood where her exotic beauty captured the attention of the American public. Lamarr was a self-taught inventor in her spare time, improving the traffic stoplight and inventing a tablet that dissolved in water to make soda. "Improving things comes naturally to me," she remarked.

During World War II, Lamarr dated pilot and businessman Howard Hughes, who allowed Lamarr to pursue her passion for inventing amidst a busy Hollywood career. He gave her equipment to use in her trailer on set and took her to airplane factories to introduce her to scientists and show her how they were built. When Hughes mentioned his desire to design faster planes for the U.S. military, Lamar purchased books on birds and fish and studied the fastest of their kind. She then showed Hughes a new wing design based on the features of these animals, to which Hughes replied, "You're a genius."

In 1940, Lamarr met composer and fellow inventor George Antheil, who shared her concern about the war. Lamarr felt frustrated simply sitting in Hollywood and making money while others were losing their lives. Antheil and Lamarr collaborated on a communications system to guide torpedos in war. The system used the technique of "frequency hopping," in which radio waves hopped seemingly at random over different communications channels instead of sticking to the same channel. This decreased interference from other signals and made messages difficult to intercept by enemies. Though this system was turned down by the Navy, an updated version of it was implemented decades later in the Cuban Missile Crisis and serves as the backbone to today's wifi and GPS systems.

When Lamarr and Antheil presented their communications system to the National Inventors’ Council, they were rejected for the system's technical feasibility. Lamarr, determined to contribute her ideas to the war effort, proposed to help the Council with her expertise in wartime technology. The Council rejected her once again, saying that as a stunning actress she would make a bigger impact acting as a spokeswoman for war bonds. Lamarr eventually ended up selling war bonds as they'd suggested.

Lamarr didn't receive proper credit for her innovative genius until nearly 50 years later. In 1997, she and Antheil received a Pioneer Award from the Electronic Frontier Foundation. "It's about time," Lamarr responded. Lamarr was the first woman to receive the Invention Convention’s Bulbie Gnass Spirit of Achievement Award and in 2014, she was posthumously inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

___

As I was researching this post, I came across numerous other names demonstrating mastery of both STEM and humanities fields—so many that I couldn't possibly fit them all into one post! I decided to split this post into two parts, and the next should be coming up later this week. I'll likely be returning to this theme in future posts as well, perhaps even making a part three or part four.

Thank you for reading and I hope you all are staying safe and social distancing during the quarantine. Feel free to comment, subscribe, and send suggestions as to what topics or figures I should cover next!

Comments

Post a Comment